There is something to be said for consistency, for knowing exactly what’s in your favorite bottle of whiskey every time you pull it from the liquor store shelf. In fact, the promise of reliability helped transform whiskey from a product of convenience to a product of preference.

Whiskey drinkers today are fiercely loyal, often seeking out specific styles, brands, and flavor profiles they trust, whether based on one past experience or a thousand.

Modern distillation has evolved in service to that consistency. Whiskey makers have perfected the process, armed with historic knowledge and advanced technology. Yeast strains are carefully cultivated and perpetuated for generations. Temperatures in fermentation tanks, stills, and warehouses are precisely manipulated to fine-tune a spirit’s flavor and viscosity. Sensors on every piece of equipment—even barrels—monitor the precise details that shape a whiskey’s final outcomes.

Modern distillation is a masterclass in repetition, but that’s not entirely what whiskey-making is about.

At its core, distillation is an iterative process, an experiment shaped by variables that can never be fully controlled. A distiller never really knows what will happen when new make spirit goes into the barrel. They can’t; wood, climate, time, and chance all play their part. The modern blender’s job is to manage those outcomes, to mix and tweak and play with the spirits until the whiskey transforms into something intentional.

Sometimes that means a batch that tastes exactly like the last, and like a hundred batches before. Other times, honoring the spirit means letting it change.

That’s precisely the case in Lexington, Kentucky, where Head Blender Dave Bob Gaspar has subtly—but deliberately—shifted the profile of Town Branch 7 Year Kentucky Single Malt Whiskey.

I know this whiskey well. I worked at Town Branch for nearly a year after relocating to Lexington in the summer of 2024. I was drawn to the distillery specifically because it produced a single malt, but quickly realized that it wasn’t my favorite expression in the brand’s core lineup.

This wasn’t a failing of the whiskey so much as a matter of personal taste. I gravitate toward whiskeys with earthy, herbal or spice-forward notes—Town Branch Rye, for example—while the distillery’s single malt leaned decisively into citrus and fruit.

Personal preferences aside, I encouraged guests to try it on every shift. As a tour guide, my role wasn’t to curate the tasting to my palate, but to help visitors discover theirs. And plenty of them did; more than a few left with a bottle of single malt tucked under their arm.

In December, I found myself back at the tasting bar—though on the opposite side. This time, I was a guest, invited to sample some of Town Branch’s newest expressions. When Dave Bob handed me a small pour of the 7 Year Old Single Malt Whiskey, I expected familiarity.

Instead, I was surprised—not only by the flavor, but by how much I liked it.

The whiskey was still 87 proof, still seven years old, dressed in its grey label and recognizably Town Branch. But the flavor was a little bigger, a little more assertive. It had a weight that I didn’t remember.

Had my palate changed, or had the whiskey?

It turns out, it was the whiskey.

Dave Bob was pouring from a brand new bottle, its contents recently awakened from their oaky slumber. He noted my surprise, and explained that the shift was intentional.

In Town Branch’s early days, founder Dr. Pearse Lyons had envisioned—and created—a softer, smoother spirit. Dr. Lyons was Irish by birth and by whiskey training, and while he chose a double distillation process for his Kentucky-made whiskey (rather than the triple distillation common in Ireland), he prioritized a light, approachable fruit-flavored profile.

The approach made sense at the time, but does it still?

In Kentucky, a delicate single malt doesn’t always stand up to its bolder brethren, bourbon and rye. And so Dave Bob set out to evolve the spirit, not abandoning Dr. Lyons’ vision, but reinterpreting it. It’s not a new distillate or proof or even age statement; instead, Dave Bob is working within the confines of whiskey distilled more than half a decade ago, incorporating older barrels to tease bolder flavors from the blend.

The result is a single malt whiskey that can stand on its own—and a mixing glass.

Tasting the (New and Improved!) Town Branch Kentucky Single Malt Whiskey

In the glass, Town Branch’s Kentucky Single Malt Whiskey is noticeably pale—it’s, by far, the lightest expression in the entire Seven Days of American Single Malt Whiskey lineup. That color—or lack thereof—comes from the barrel.

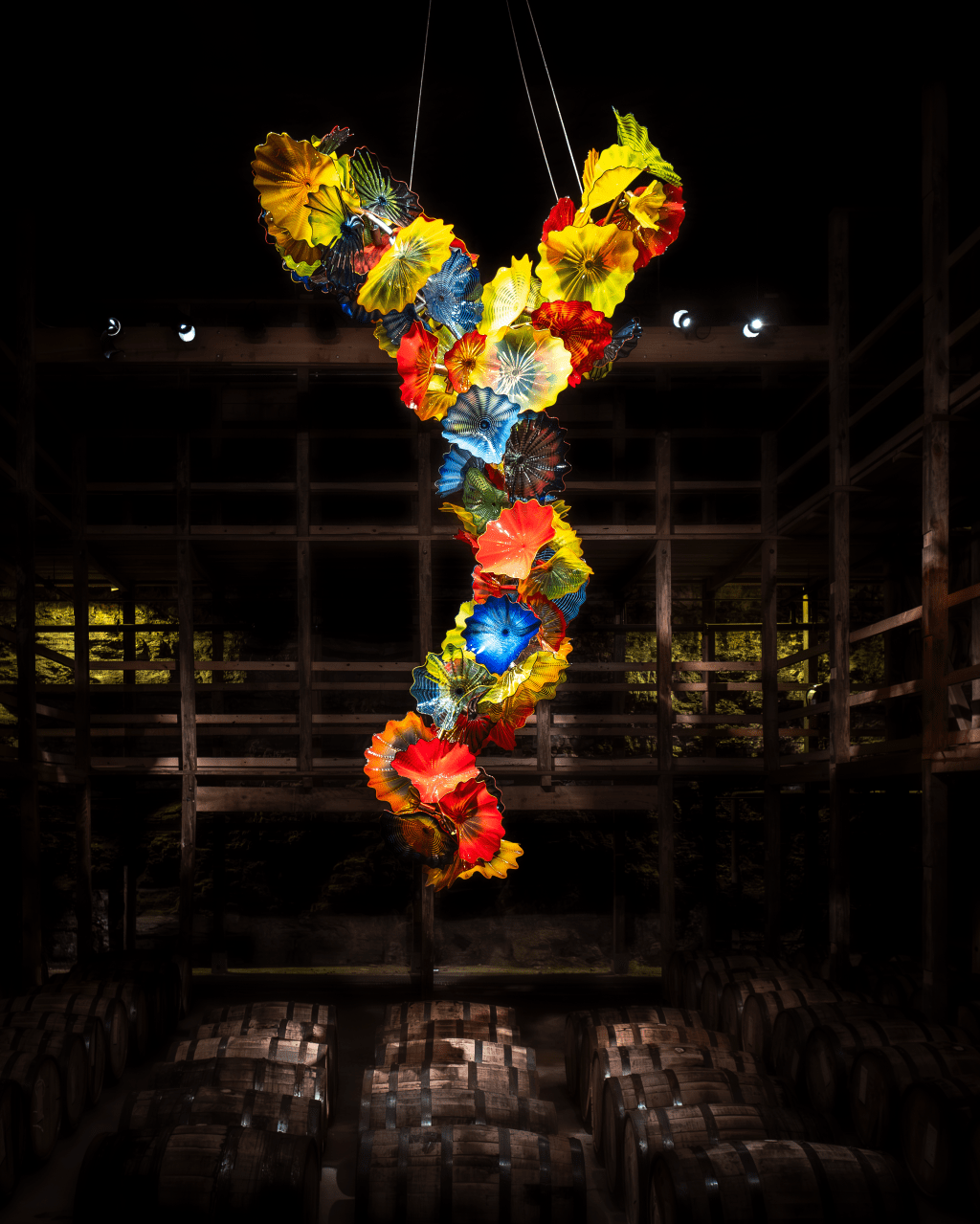

As the distilling part of Lexington Brewing & Distilling Company, Town Branch’s stills operate just steps from Lexington Brewing, where Kentucky Bourbon Barrel Ale is made.

Barrel aging beer was one of Dr. Lyons’ signature innovations, and has come to define the brand for more than two decades. It also means that barrels at Lexington Brewing & Distilling follow a unique path, traversing Cross Street from the distillery to the brewery and back. First, the new oak barrels are filled with Town Branch Bourbon. Four to six years later, the barrels are emptied and filled with Kentucky Irish Red Ale, transforming it into the flagship Bourbon Barrel Ale. After that, the barrels hold one of the brewery’s cream ales: vanilla or tangerine. Only then are the thrice-emptied barrels filled with single malt new make spirit and left to rest for at least seven years.

The whiskey that emerges is light gold in appearance. It opens to the nose with citrus fruit, vanilla, and malt, like the rich sweetness of a pineapple upside-down cake.

On the palate, that fruit blooms into ripe and juicy flavors. There’s a touch of almond, or almond extract to be exact, and a viscous-yet-light mouthfeel.

The finish tingles and lingers on the tongue, a flash of deeper fruit notes and baking spices. There’s also a hint of beer, a little bit of funkiness pulled from the depths of the well-used oak. It’s not unpleasant; it adds character, an extra bit of depth.

All told, Town Branch Kentucky Single Malt Whiskey is bright, refreshing, and wholly different from any of the other whiskeys included in this series.

It’s also different from its former self. Which, some might say, is the point.

Slainte, y’all.

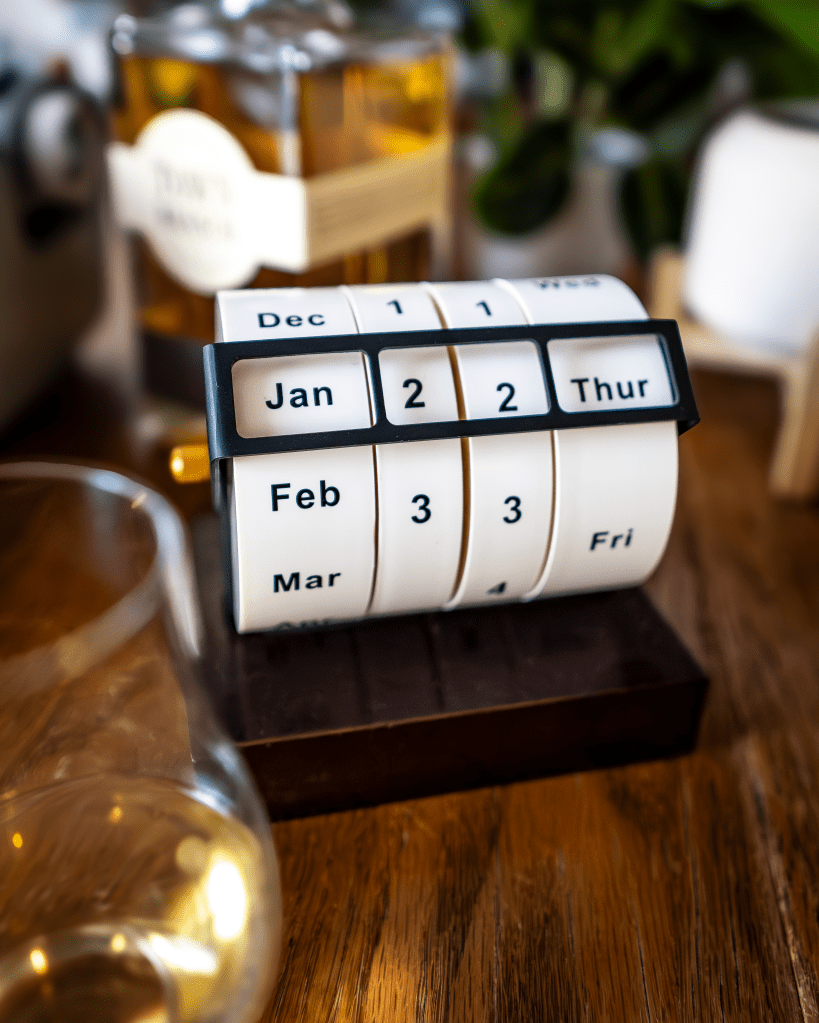

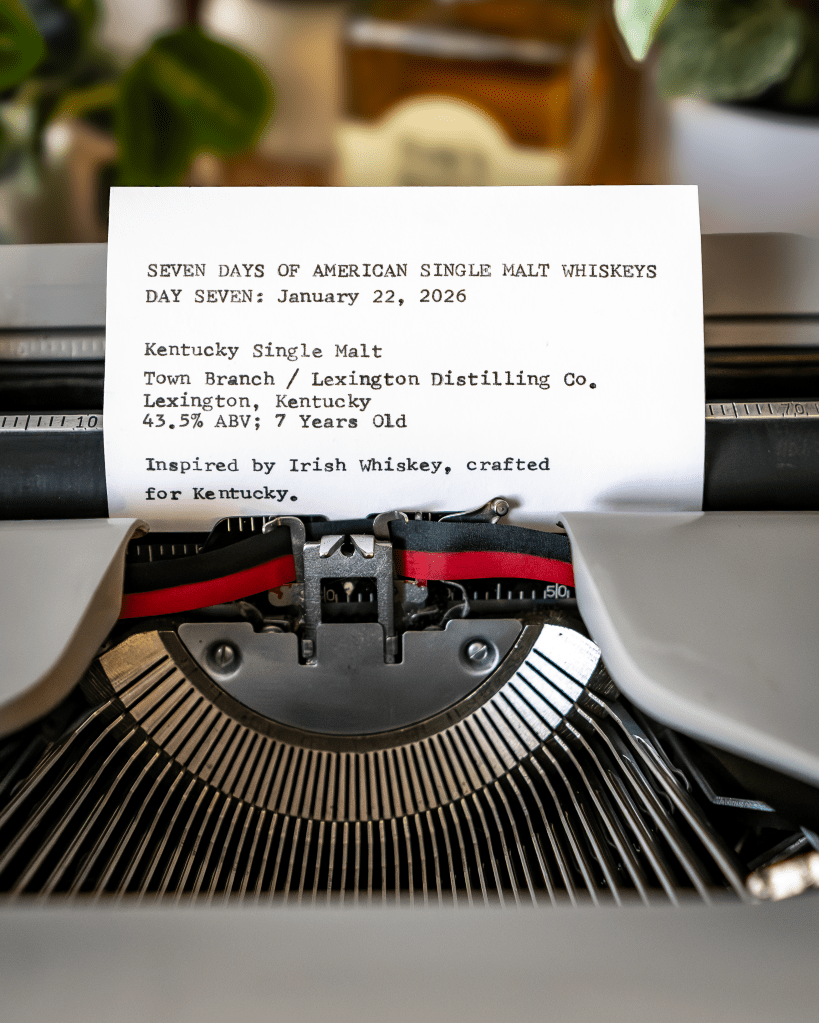

In My Glass

Kentucky Single Malt Whiskey

Town Branch/Lexington Distilling Co. – Lexington, Kentucky

43.5% ABV; 7 Years Old

On My Desk

Royal Futura 600 Typewriter

Read More from the Seven Days of American Single Malt Whiskey 2026

- Day One: McCarthy’s Oregon Single Malt Whiskey

- Day Two: New Riff Sour Mash Single Malt

- Day Three: Stranahan’s Mountain Angel 12 Year

- Day Four: Redwood Empire Foggy Burl Single Malt Whiskey

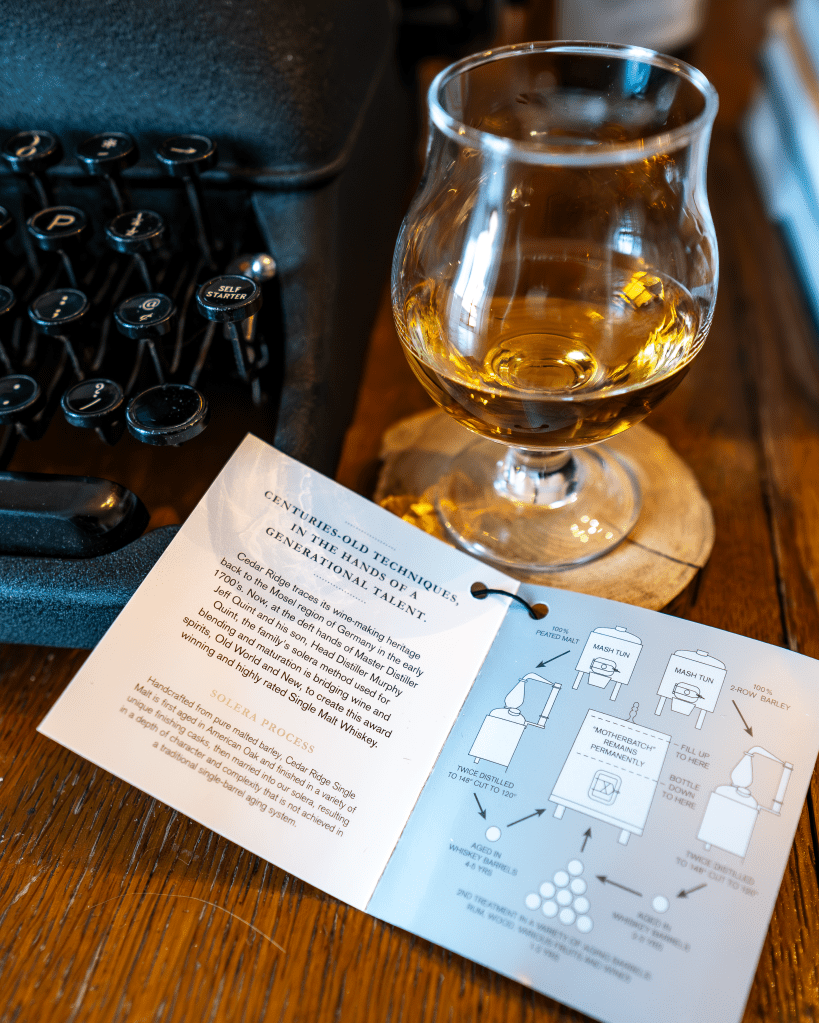

- Day Five: Cedar Ridge The QuintEssential Signature Blend (Batch 017)

- Day Six: Whiskey Del Bac Club Blend 2025

A Note of Gratitude

This bottle of Kentucky Single Malt Whiskey was given to me by Dave Bob and the team at Town Branch. Thank you for letting me sample and share the new and improved single malt!