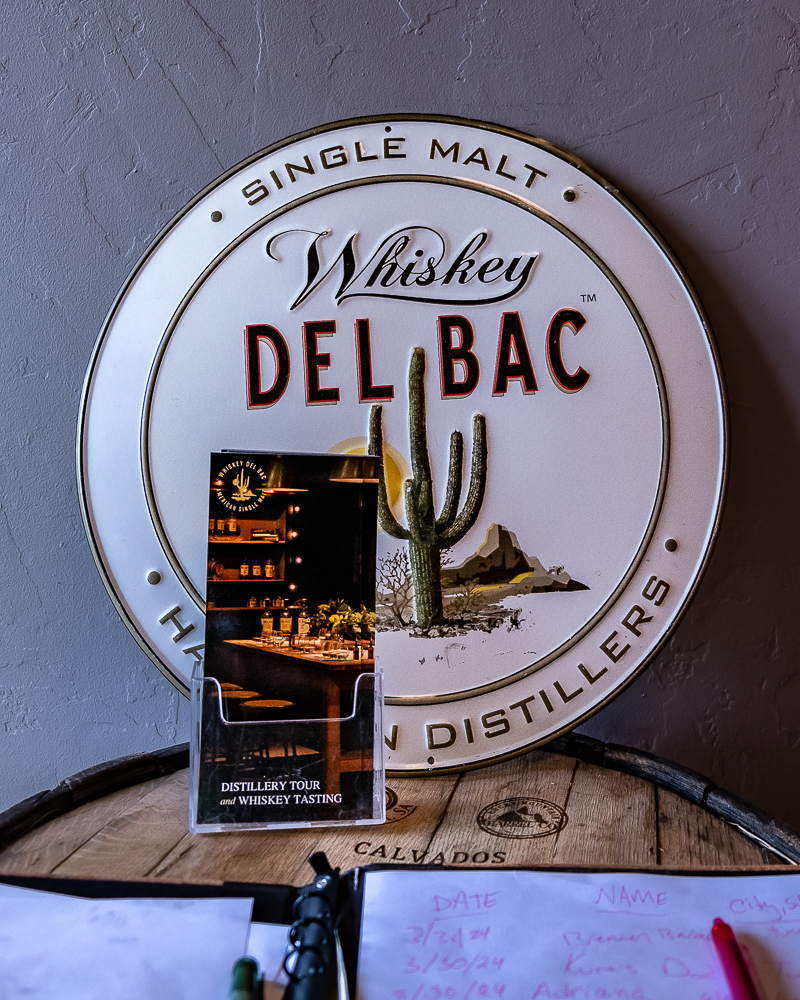

If you’re not actively looking for Whiskey Del Bac’s award-winning distillery in Tucson, Arizona, you’re not likely to find it. Nestled against the I-10 highway in an industrial park on the west side of town, only an understated decal to announces its front door.

Of course, for those who know about whisky (or even about craft beer), the massive silo on the back of the building is a dead giveaway that something is brewing inside the otherwise unassuming walls.

That silo holds some 50,000 pounds of unmalted barley, waiting and ready for a trip into the drum malter inside. Until a couple of years ago, Whiskey Del Bac (more formally known as Hamilton Distillers) only produced American Single Malt Whiskey. Like most modern single malt distilleries, they source the majority of their barley ready to be milled and mashed. But when founder Stephen Paul began to fiddle with the idea of making whiskey, he had a particular outcome in mind, which required him to malt his own barley, even as an amateur distiller.

That idea is now bottled and named Dorado, a mesquite-smoked single malt whiskey that, as I used to tell guests at the distillery, is more akin to a campfire than a boat fire.*

That’s a good way to segue into my disclaimer for this post: for six wonderful months between the fall of 2021 and the summer of 2022, I was employed by Whiskey Del Bac as a tour guide. For two or three days every week, I led guests through the history and production and experience of the distillery’s core range of whiskies, including Dorado. I’ve always looked back on that time fondly, and I’m still friends with many of the distillers, managers, and sales folk who remained.

I am no longer paid by Hamilton Distillers, but I’ve continued to be an enthusiastic advocate for what I truly believe to be one of the best American Single Malt Whiskies money can buy.

How Whiskey Del Bac Came to Be

Whiskey Del Bac was founded by Stephen and Amanda Paul, a father-daughter duo who are still involved in the distillery’s strategy and operations.

Unofficially, it was Stephen’s wife who deserves the credit for this American whiskey.

Stephen is a carpenter and a furniture maker by trade. For years, he owned a custom furniture shop on Tucson’s Fourth Avenue, a lively and iconic street in the Old Pueblo’s downtown area. Embracing the spirit and the natural resources of the Sonoran Desert (of which Tucson is a part), Stephen frequently employed mesquite wood to build his creations.

Mesquite is a hardwood that grows across the American Southwest. Both beautiful and dense, it is often compared to fine woods like oak and walnut. That makes it a phenomenal choice for furniture—and for smoking meat, which is, indirectly, how Whiskey Del Bac came to be.

The Pauls were (and are) scotch whisky drinkers. They also would utilize the off-cuts of mesquite wood from Stephen’s shop to smoke meat at home. Legend says that on one such night in the backyard, with a rich cut of beef (or something similarly meaty) on the smoker and a glass of scotch in her hand, Elaine wondered aloud whether one could smoke malted barley with mesquite rather than peat.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Whiskey Del Bac’s Core Range: Smoke, No Smoke, and Rye

At the spiritual heart of Whiskey Del Bac’s core range is Dorado, a smoky single malt whiskey that’s “mesquited, not peated.” It’s the whiskey for which the distillery is most well-known, at least in Tucson, where the marriage of local ingredients and local whiskey frequently receives high praise. Dorado offers a unique combination of sweet mesquite smoke and the bold vanilla-and-caramel flavors characteristic of new American Oak barrels.

Two other expressions, the Classic and the Sentinel, round out the distillery’s main offerings.

The Classic is a straightforward whiskey distilled from exclusively unsmoked barley, modeled in quality after a revered Speyside scotch like those from Macallen or Balvenie. It’s also the best of the distillery’s three main whiskies—and that’s not just my opinion. In the last few years, the Classic has earned an enviable 90 rating from Whisky Advocate and a 93 from sister publication Wine Enthusiast. The latter also listed the Classic in its Top 100 Spirits of 2021.

Sentinel, the distillery’s singular rye whiskey, is the only one of Whiskey Del Bac’s offerings not fully produced on site in Tucson. The raw spirit is distilled in Indiana before being transported to the desert to rest in Del Bac’s casks. The team uses ex-Dorado barrels to age the spirit, infusing the spicy rye with soft notes of mesquite smoke.

Beyond the core range, the distillery produces some seven (or more) special releases every year.

Normandie, Frontera, and Ode to Islay (my personal favorite) are annual limited releases. The three expressions utilize a brandy barrel finish, a Pedro Ximenez sherry cask finish, and a veritable crap-ton of mesquited barley, respectively.

The remaining releases are seasonal. The Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall Distiller’s Cuts vary from season to season and year to year. As head distiller Mark A. Vierthaler recently explained at a distillery open house, these distiller’s cuts allow his team space for creativity in an industry that otherwise thrives on consistency. The most recent quarterly expression, the Spring 2024 Distiller’s Cut, features “an unsmoked base matured in New American White Oak, finished in Tawny Port barrels, then blended with mesquite smoked American single malt petites eaux from a used bourbon barrel” according to Whiskey Del Bac’s website. The description is a mouthful, but so is the dram.

Next spring, it’ll be entirely different, a yet-unseen product of the distillers’ imagination.

Touring Whiskey Del Bac

Whiskey Del Bac still falls firmly in the “craft” category of distillation, filling a relatively small space with a single 500-gallon pot still and various other necessary equipment.

When you tour the distillery, you start in a narrow corridor between the shop and offices and the production floor. Here, you’ll see one of Stephen Paul’s handcrafted chairs, early iterations of the whiskey’s labels, and, currently, a handmade mill. During my time as a tour guide, the small room housed Paul’s original and intermediate stills, both curvy copper pots with a capacity of five and 60 gallons, respectively.

It’s here that you learn about Whiskey Del Bac’s original inspiration, and how Stephen’s drive for creation and quality led him down the path to the whiskey we know today. You’ll also learn about how Amanda, freshly returned from New York City, got involved—specifically by urging her dad to formalize his whiskey-making activities rather than be arrested for illegal moonshining.

From this ad hoc and ever evolving museum, you move to the back of the building, listening to the creaks and sighs of the equipment and systems. The tour guide, Ian in my case, will explain the malting process, performed here on a drum malter. He talks about the grain and the acrospsires and the smoke that are essential to the malting process, as well as the mechanics of moving it all from one tank to another.

Then it’s on to the mill and the mash tun and the business of making whiskey in earnest. If you’re lucky (or ask), you can taste the newly fermented distiller’s beer, which is not particularly palatable in terms of beer, but also not terrible either.

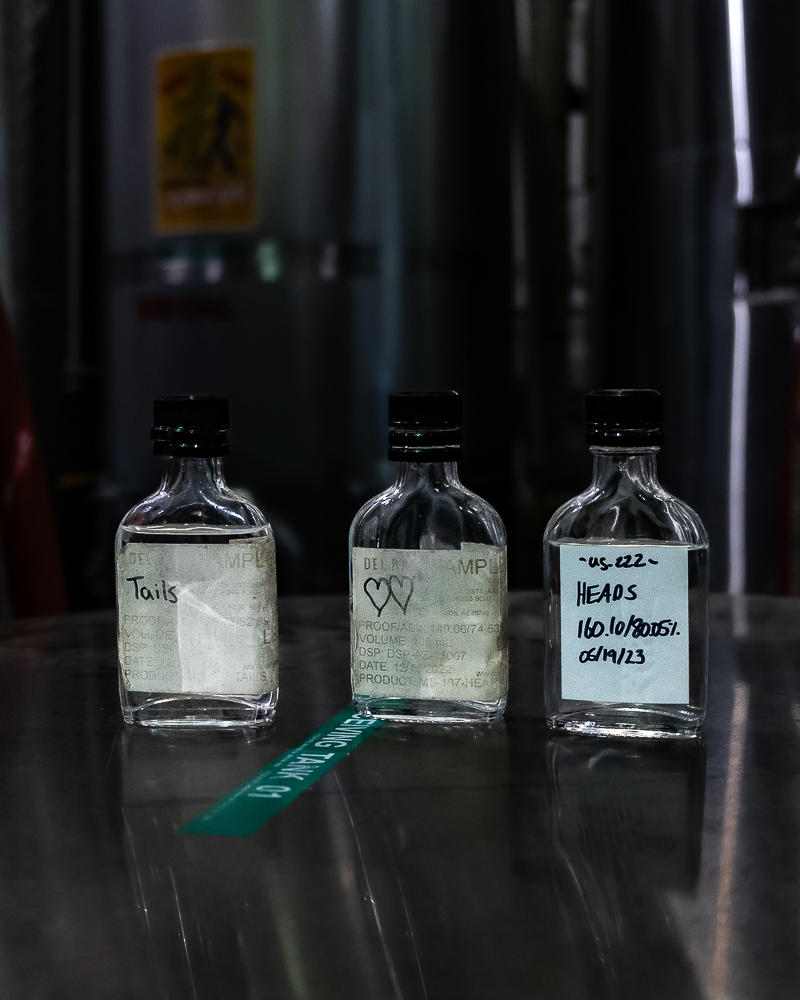

After the still and a discussion of the heads, hearts, and tails, it’s on to the barrels, which includes both the large finishing casks (rhum agricole, sherry, tequila, cognac, brandy, and more) and the standard new American oak quarter casks, inside of which every drop of Whiskey Del Bac begins its maturation journey.

Somewhere around the barrel area, our tour gropu was graced by the presence of Two-Row, a grey tabby cat who lives at the distillery full time. As head mouser, occasional greeter, and official mascot of Whiskey Del Bac, Two-Row loves to offer her two cents on every tour—and her two front paws to every tasting, often sipping them into unsuspecting guests’ water cups.

The tour finishes with a brief nod at the bottling area and then a settling into the tasting room, which, if we’re honest, is the primary reason anyone comes on these tours. Spread around two large rustic tables, you can try the three core expressions (Classic, Dorado, and Sentinel), and then, if available, any current limited releases. On my tour we sampled both the Frontera (an unsmoked barley malt finished in PX sherry casks) and the Spring Distiller’s Cut (see above).

Of course, every good tour exits through the gift shop. Or, in this case, the whiskey shop, where you can stock up on bottles and other bits and bobs. You’ll even find t-shirts emblazoned with the distillery’s mesquite, not peated motto.

As you shuffle back into the sunshine, laden with whiskey in paper bags, the bright heat and cacti of the Sonoran desert await. The landscape is harsh and unyielding, but among the scrub and the dust you’ll also find strength and beauty. This, truly, is the spirit of Whiskey Del Bac.

Slàinte, y’all!

*My fellow Islay whisky drinkers (and haters) will understand that reference…and most of my guests did too.