It’s day three of the 2026 Seven Days of American Single Malt Whiskey series, and I have a confession to make: I didn’t like Stranahan’s Rocky Mountain Whiskey the first time I tasted it.

The thing is, there are certain American Single Malt expressions that lean hard into a banana bread flavor profile. I’ve asked a few distillers about the source of this particular note, and the answer is always the same: it’s a combination of factors. Yeast selection. Fermentation methods. Where the cuts are made off the still.

It’s all science and taste and artistry tied together. Absolutely fascinating, of course.

But I just don’t enjoy it.

It’s odd, too, because I love banana bread.

I still have my grandmother’s handwritten recipe card in my kitchen, nearly 20 years after her death. She made it often, using up whatever rapidly-browning bananas were sitting on her counter. She would even send me a loaf or two when I was in college. I would warm a slice in the microwave, slather it with butter, and enjoy a little taste of home.

But one thing that I’ve discovered throughout my whiskey journey is this: while I may love something on a plate, I don’t always like it in a glass.

Banana bread is the perfect example, and it was that flavor profile that dominated my first experience with Stranahan’s Original Single Malt Whiskey. But with so many other whiskeys in the world to explore, I simply labeled the spirit as “not my favorite” and moved on.

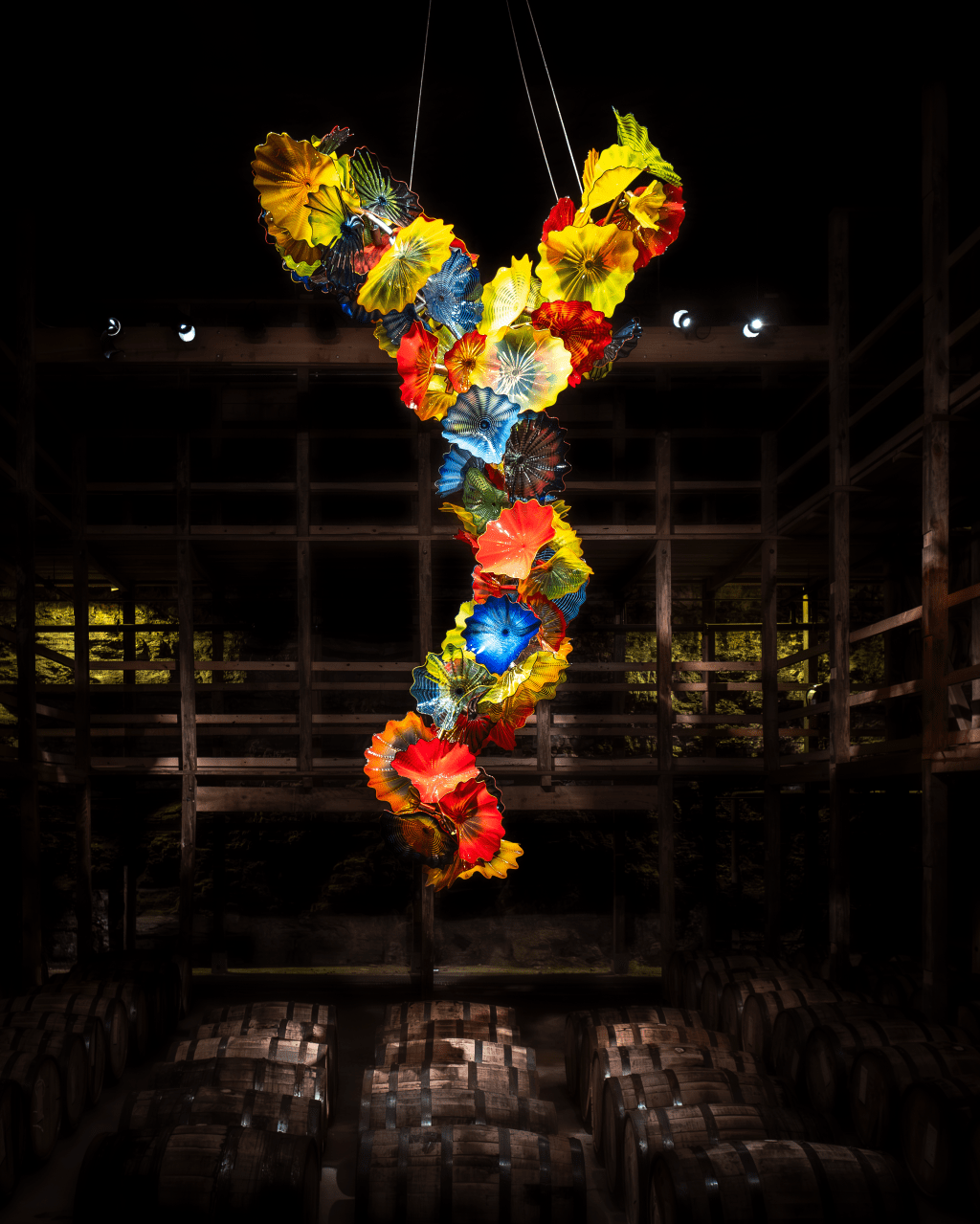

Until a few years later, when I found myself in Stranahan’s Denver Distillery.

I had flown up from Tucson, Arizona to attend an event with the Scotch Malt Whisky Society, and I figured I ought to make the most of the plane ticket. Despite my skepticism toward Stranahan’s (unfairly assigned after one tasting of one expression), I was excited to visit another ASM distillery, so I booked a tour.

Walking through the facility—one of the largest, if not the largest, single malt-focused distilleries in the country—I learned about its history and processes. While Stranahan’s wasn’t the first to make an American Single Malt Whiskey, they are among the oldest. Their first whiskey was released in 2006, nearly 10 years after a barn fire sparked an unexpected friendship between a local brewer and a volunteer firefighter.

That fire connected local whiskey enthusiasts Jess Graber and George Stranahan, who together developed the recipe for what would become Stranahan’s Rocky Mountain American Single Malt Whiskey. Graber officially founded the company in 2004, naming it after his friend. It was the first (legal) distillery in Colorado since prohibition.

Today, Stranahan’s proudly calls itself the #1 American Single Malt. It’s a bold claim, but not without merit. After 20 years of production, they are the most awarded distillery in the American Single Malt Whiskey category. Building on the success of the Original, they offer a full range of small batch single malt whiskeys, which are available for sale in their Denver brand home and across the country.

I tasted a few of those whiskeys—including one or two limited distillery exclusives—at the end of my 2023 tour. Standing in the Stranahan’s distillery tasting room, I learned a very important lesson:

Never, ever judge a whole distillery by a single expression.

As it turns out, I like Stranahan’s just fine, thank you very much. And I’m genuinely excited to include them in this year’s Seven Days of American Single Malt Whiskey series. Especially because the expression they sent me, the Mountain Angel 12 Year, was recently awarded the #16 spot in Whisky Advocate’s Top 20 Whiskies of 2025.

Yes, please.

Tasting Stranahan’s Mountain Angel 12 Year Single Malt Whiskey (Batch 2)

If you’ve ever wondered where the angels might be the happiest, look to the skies above Denver, Colorado. The city’s high altitude, dry air, and dramatic temperature shifts all wreak havoc on aging whiskey. Evaporation accelerates as barrels breathe deeply and the angel’s share climbs, leaving far less in the barrel than one would prefer.

For the Mountain Angel 12 Year, the angel’s share reaches nearly 80%. A shocking four-fifths of every barrel disappears into the air in just over a decade. What remains is bottled as the distillery’s “rarest expression,” produced in limited runs and released in small batches.

My bottle is from Batch No. 2, numbered as 9,653 out of 16,800.

(Okay, it’s not a tiny run of whiskey, but I told you they were pretty big.)

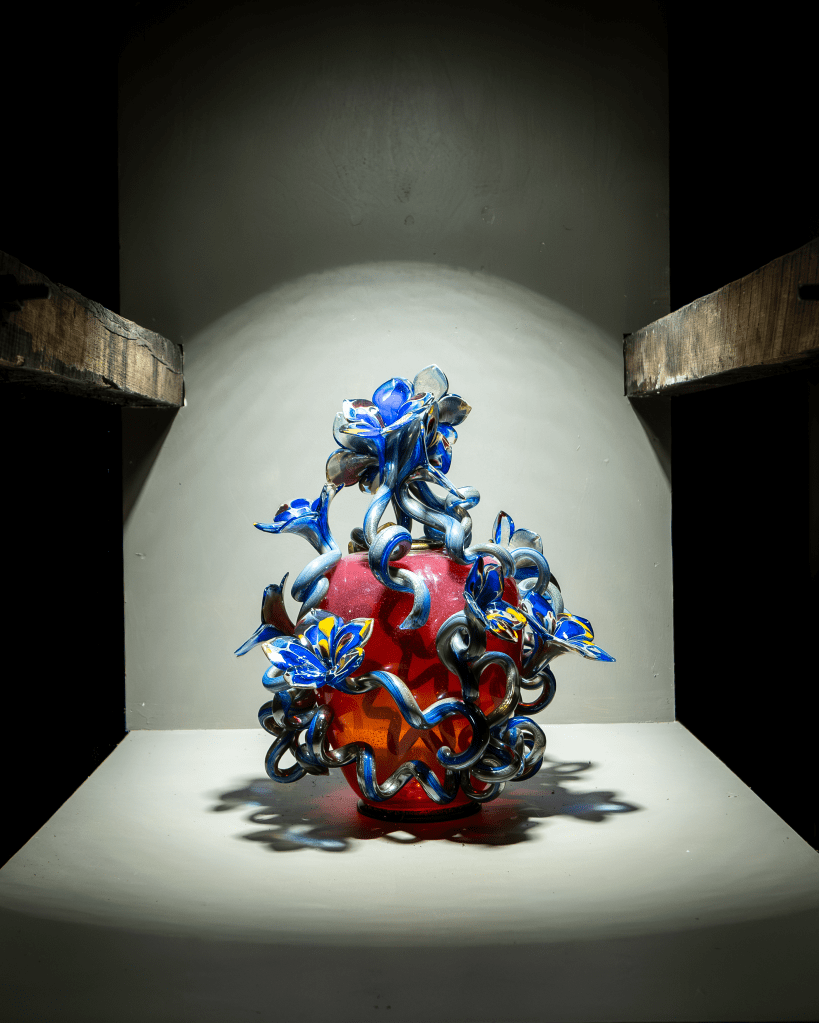

For a whiskey category that’s barely three decades old, a 12-year age statement is not insignificant. Stranahan’s uses local barley—Colorado being one of the few states where the crop thrives—and crisp Rocky Mountain spring water to produce their spirits. This particular whiskey is aged first in new American Oak barrels, then finished in port wine casks.

On the nose, I get rich, ripe fruit, sweet and potent. Yes, there’s still a whisper of banana bread, but it’s refined now, not heavy or overbearing. After a swirl, the whiskey slides back down the glass at a moderate pace, not too thick and not too thin.

The first sip is surprisingly light, not entirely what I expected from a port wine-finished whiskey. It’s rounder and fuller than the legs would suggest, and the flavor flows in waves, notes of fruit and pastry coating the tongue before settling into an oaky, tannic finish.

At 94.6 proof, it falls in what I consider the sweet spot for most single malt whiskeys. Still, I wonder about its potential at a slightly higher ABV. I wouldn’t mind a little more intensity, a stronger punch of flavor on the palate.

As it stands, it’s well-balanced, and likely appeals to a wider audience at 94.6 than it would at 100 proof. Mountain Angel is also a remarkably smooth whiskey, with enjoyable nuance and depth to it.

Thank goodness the angels didn’t take it all.

In My Glass

Stranahan’s 12 Year Mountain Angel Single Malt Whiskey (Batch 2)

Stranahan’s Colorado Whiskey – Denver, Colorado

47.3% ABV; 12 Years Old

On My Desk

1961 Smith-Corona Skyriter (purchased online from a Colorado Goodwill!)

Read More from the Seven Days of American Single Malt Whiskey 2026

Day One: McCarthy’s Oregon Single Malt Whiskey

Day Two: New Riff Sour Mash Single Malt

Day Four: Redwood Empire Foggy Burl Single Malt Whiskey

A Note of Gratitude

This bottle of Stranahan’s American Single Malt Whiskey was sent to me by the folks at the distillery, who I did not tell about our rocky start. Thank you to the team for letting me taste and share their wonderful whiskey!